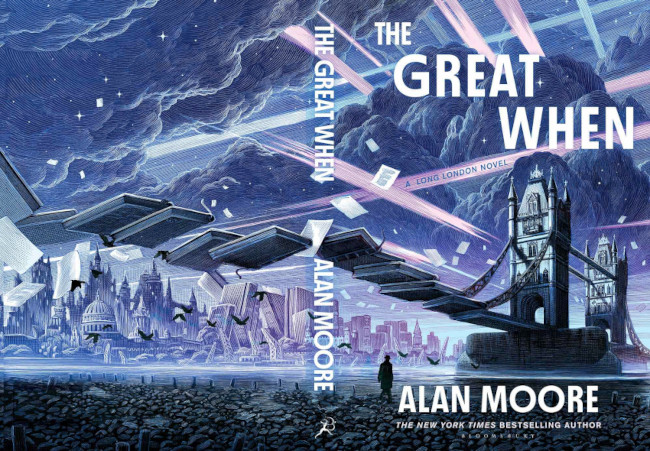

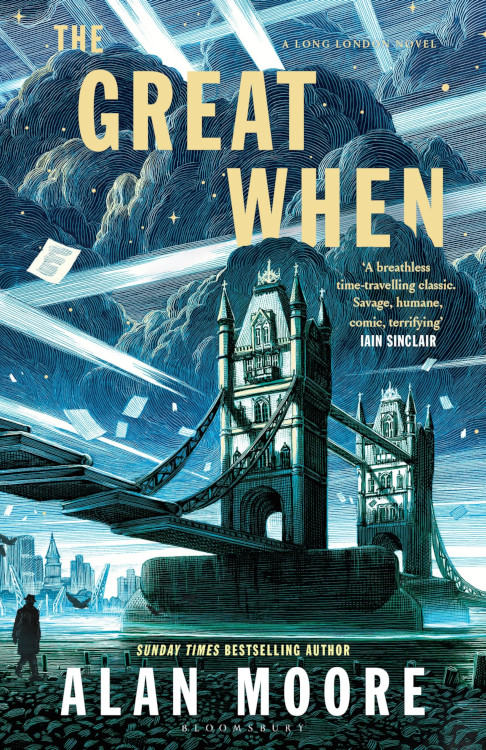

Alan Moore’s latest novel, The Great When, begins a series of five stories set in London, each set in a decade following the Second World War. The purpose of this cycle, “The Long london”, is to establish a reflection on our present from this look at the past, “as a psycho-historical journey of how we got here,” as he explains in an interview.

The author thus continues his literary career through novelistic construction after particularly striking creations in the field of comics or rather graphic novels, a genre he helped to create. We think of Watchmen and V for Vendetta , but also From Hell, Swamp Thing… Familiar with the novel since 2008, he inserts himself here into this rich tradition of another London, a parallel one, an “inferior” city hidden under appearances, like a sub-world which is nevertheless the source and truth of the “ordinary” city. The most obvious reference in this literary tradition is Neverwhere, by Neil Gaiman, which is never mentioned… Unlike Michael Moorcock and Iain Sinclair with whom Moore collaborated, he dedicates the work to them.

The purpose of this article, beyond a simple presentation of the novel, is to situate the main historical figures to whom Alan Moore pays homage, and from their roots in magical and esoteric traditions, to situate the philosophical foundations of the surprising world with which the author confronts us: a very personal idealism.

Version française originale disponible

1 – How it all begins

The very title of the novel, The Great When, is a subversion of a long-standing, unflattering nickname for the city of London. Beyond the play on words, the title refers to a question about time as forgetting, and the persistence of a past that is the very being of the city, particularly if the story takes place in a largely destroyed London in the aftermath of World War II. In fact, there is… a lot left of the past.

The introduction to The Great When, which is that of the entire cycle to come, introduces us to a mosaic of colorful characters in picturesque, even animated situations, without respecting any chronology.

In the beginning there is magic, does this novel tell us about something else?

It is the meeting of two dying sorcerers, which marks the end of an era: Alistair Crowley is visited by Violet Firth, better known as Dion Fortune. If the na

mes are only allusive (Crowley’s is not mentioned), we do find the sorcerer’s servant or assistant under the name of Kenneth Grant. The esoteric order of the Golden Dawn, which is not mentioned, permeates this presence of the past. Moina Mathers, artist and occultist, sister of the French philosopher Henri Bergson and founder of the order is mentioned. Dione Fortune will die of leukemia in 1945, a few months after this meeting. Crowley has only two years left to live. The impending death of these two characters is like the disappearance of an England destroyed by the war on the ruins of which a new world begins to be built, but can we wipe the slate clean of the past?

The years do not follow one another but intertwine in this strange introduction. Then comes David Gascoyne, surrealist poet, anti-fascist and member of the communist party. He has a vision of the great When before the war, a monster that no one sees except him in the 1930s, during a protest that goes wrong. Does this vision contribute to the source of the surrealist dimension of his art? In this novelistic, fictional context, without a doubt. As the author constructs a metaphor for the real world, the now classic idea that the painter shows what is invisible to ordinary eyes is to be taken in a strong sense.

Let’s go back even further into the past, still without any date being given. Another character, still as colorful as ever, appears : Prince Monolulu, who predicts the victory of the horse Spion Kop. This takes place at the 1920 derby. The character is so fanciful that the uninitiated reader will certainly believe he is in pure fiction, and yet…

Finally, the unusual name of Dennis Knucleyard was dreamed up by the author. He is the main character, who is fictional. At the end of this complex introduction, the year is 1940 and Dennis, who is then only 9 years old, witnesses the destruction of Cripplegate by Nazi missiles. He is then given a vision of this parallel London and of a strange character who watches this destruction in amazement from the door of an arch that no longer exists.

2 – Characters, places and objects

Nine years later, Dennis is trying to survive in a difficult post-war world. He’s staying with the colorful and coughing Coffin Ada and working for her second-hand bookstore, Lowell’s Books & Magazines. He’s in charge of stocking the bookstore with stuff and is tasked with picking up a batch of Arthur Machen’s books. Among these is a non-existent, fictional work, which is only mentioned in one of Machen’s last novels, N: A London Walk (1853) by the Reverend Thomas Hampole. And yet Dennis does have this book in his hands. Among a small pile of books by a writer he’s never heard of is a fictional object, one that doesn’t exist, and he knows nothing about it. On his way home with his parcel of books under his arm, Dennis spends the time in a pub with Clive Amery, one of his two friends. Then he meets Grace, a young prostitute who is the second female character in the story, in total contrast to Coffin Ada. She realizes the next day that one of the books is a fake, that it cannot exist, and she asks Dennis to bring it back. It is then that Dennis will have a bad encounter with Jack Comer, but this impossible book will take him to another world: the Great When, a parallel London of which many characters have knowledge if not a premonition, starting with Coffin Ada who does not detail anything.

Dennis will meet a very important number of real people to whom the author pays homage, such as Iron Foot Jack. It is difficult to mention them all, one might regret that Moore simply mentions in chapter 3 the name of Algernon Blackwood, another member of the Golden Dawn and great writer, still living in London in 1949. There is just his name in chapter 3.

It’s hard to say more without giving away more of the plot, so let’s move on to analyzing the meaning of this whole construction (we don’t go beyond the presentation on page 4 of the cover, though…). Note, however, that everything really begins at this point, with an alteration of the narrative that moves to the present tense, written entirely in italics. Alan Moore explains:

“Italics, for some reason, make things more intense. They’re leaning forward, they look like they’re in a hurry to get somewhere. It was to make people feel that they were suddenly in a different state of being and that perhaps not one that they were necessarily comfortable with” (interview, Entertainment Weekly).

The passage into this other world of the Great When is a physically disturbing experience, the opposite of Narnia’s closet, among so many other examples of parallel universes.

“If any of us were to even fleetingly contact a world with different physical laws, we would be in therapy for the rest of our lives. It would be a shattering experience, and so that’s what I’ve tried to get across in The Great When, where the characters’ reactions when they go into or out of the other dimension generally includes vomiting, weeping, and fainting (Ibid).

Here is one of the first visions of this elsewhere which seems to be a nightmarish hallucination:

“Filtered through twinkles, he sees urban landscape writhing at the brink of ravenous biology… peony lampposts that have petals cast in wilted glass drop on gunmetal stems, and hanging cables squeak black rubber leaves… eye-corner movement, rustlings in a turf of quivering litter, caterpillar Durex, not a thing that is not animate… he tries a few steps but his legs are wobbling, and out of unsources glimmer, there are crabs of broken crate whose eight limbs are articulated splinter; moths folded from nudie magazines with bozons printed grey on water-damaged wings, a creep of fag- ends maggots”

This experience undeniably contains the psychedelic elements to which Moore is heir, in this distortion of ordinary reality and the creation of composite entities, even if there is no insistence on the alteration of the colors of this parallel London.

3 – Interpretations

What is the meaning of such an experience? How can we understand this passage into a world that can be more real than our own, in its relationship to magic? What is real? What should we understand from what Alan Moore, artist and magician, shows us?

We can begin to get an idea of this from the writers and artists that Moore calls upon, starting with Arthur Machen (1863 – 1947), at the heart of the entire cycle of 5 novels to be varnished which will extend until the end of the 20th century. Also a member of the order of the Golden Dawn, Machen is one of the great authors of fantasy of the 20th century. Best known for The Great God Pan (1894), he published numerous texts including The Hill of Dreams (1897) and The White People (1904). Lovecraft pays him a strong tribute in his essay Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927 – 1934). John Gawsworth, Machen’s editor, in particular of his last works including “N“, is part of the plot of The Great When.

Alan Moore briefly features Machen in Dennis’s wanderings through this other London:

“Near the mouth of Surrey Street, a human figure, motionless, a young man dressed in an old man’s overcoat, his head thrown back and his arms raised as if to ignite the moment, in a shower of emerald light that falls only on him”

Has he become an Idea? Has Machen found a form of immortality, bathed in the light of this elsewhere?

The novel “N” (1934) is at the heart of the Great When. A review of it can be found at this address. We are of course thinking of Lovecraft’s short story “He“, which also depicts another world seen from a window. A vision of a world older than ours, much more pleasant and enchanted – at least initially, which has its analogues in the last pages of The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, as in the prodigious short story The Strange High House in the Mist (1926).

“N” develops the experience of what will later be called psychogeography, as a form of interior exploration linked to the discovery and exploration of places, here the London cityscape. This exploration or rather exaltation here becomes seized by a perichoresis. Arthur Machen considerably diverts a theological term relating to the interpenetration of the three divine persons, by attributing this interpenetration to that of two (or more) realities, like layers of parallel worlds which are in communication. Alan Moore will totally assume this subversion of classical theology.

However, what distinguishes his approach is the immersion of the characters in this other world, which is no longer simply seen from a window. This upheaval of reality must be disturbing, including or even especially at the cost of a strong impression of confusion in the narration explicitly assumed in order to disorient the reader.

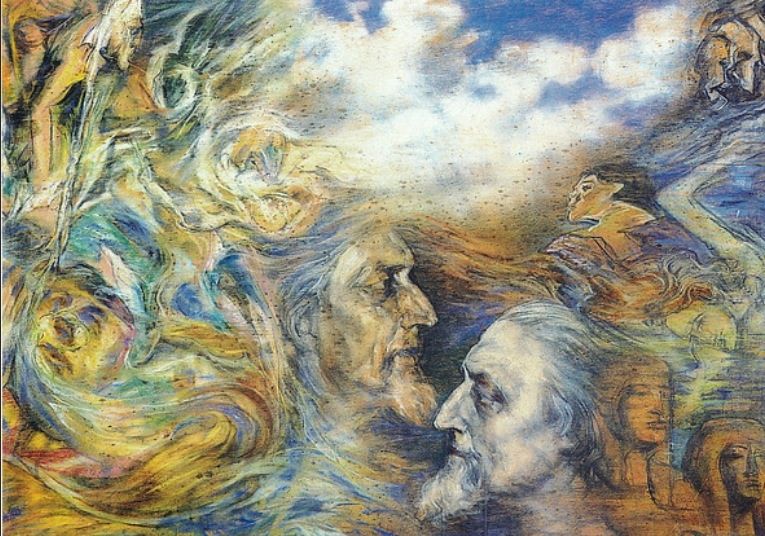

To escape his troubles, Dennis realizes he must return to the Great When, but he needs a guide, whom he will seek out. This character plays a major role, as Alan Moore is so keen to pay tribute to him.

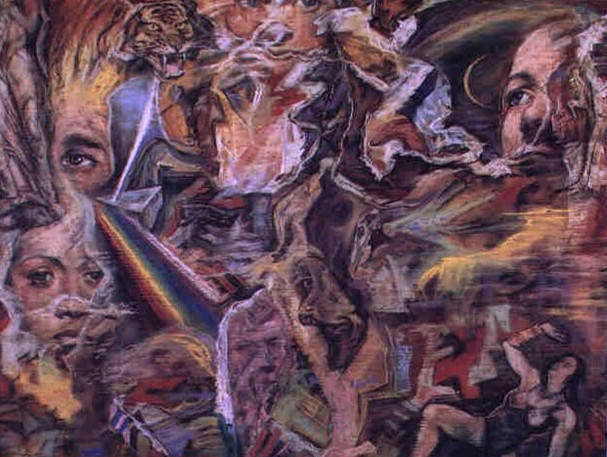

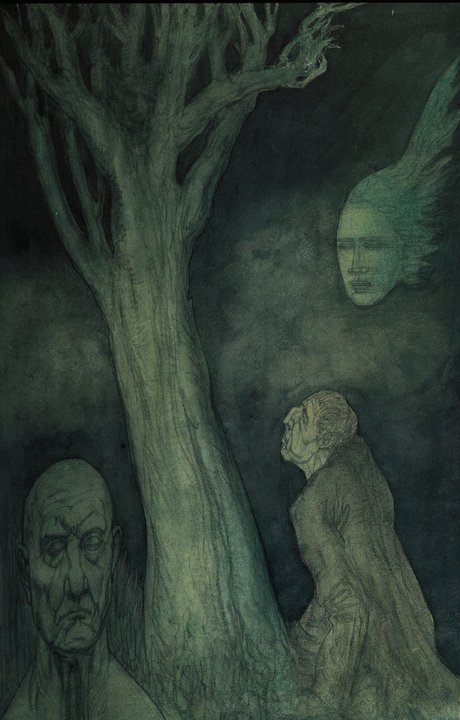

Painter and magician, Austin Spare lives in a tiny basement room that also serves as his studio following the destruction of his house during the war. His very personal art is not surrealist, and we owe him works on occultism in which he develops doctrines that are also his own, having quickly distanced himself from the Golden Dawn and Alistair Crowley.

A must-read biography of Austin Spare dates from 2011, written by Phil Baker and prefaced by… Alan Moore!

What better way to evoke this artist than to choose a few of his paintings?

In the novel, Spare also has a cupboard that accesses another reality, which he is accustomed to; he will thus guide Dennis in the Great When (pp. 178 ss). Artist and magician, aren’t they the same thing? This is not at all to be taken with a pinch of salt, Alan Moore explains it very explicitly.

“If you can manipulate your own consciousness and perhaps that of others, which is surely something that all artists wait to do whether they are magicians or not, then you will have performed an act of magic”.

A painting, like a book, is a spell, a magical work in the same way that it is a work of art. Austin Spare thus follows an approach that Moore continues.

We have studied how Alan Moore constructs a whole reflection on the being and presence of the world, of reality. In this way, he considerably subverts classical ontology and leads us to relativize the allusions to the Platonic cave that we find in the critiques of Rich Johnston and Gareth Southwell. Certainly, the common, ordinary, and everyday world is very limited. The shared perception of what we call “reality” turns out to be very narrow. That there is another reality, that it is possible to pass through the “doors of perception” as if we were prisoners of a cave, is what Alan Moore speaks to us about with such disturbing writings. However, if there is someone Plato is wary of, it is the artist, precisely the one who is for Moore the magician par excellence. But above all, the journey outside the Platonic cave culminates in a transcendence of a profoundly religious, mystical nature. This is not at all Moore’s point of view, whose ontology refers to another world, but which always remains that of human consciousness. It is ultimately the measure of everything we can call reality. If this other world that The Great When depicts for us is in a sense the source of the sometimes very dull and narrow common reality that we share, it is not at all in the mode of a creation from eternal essences. We must rather seek the source of these essences in the common world that we share, its history and the human figures who have marked it and made it as it will remain… for a certain time.

It is the godless world of an anarchist magician.

Are you sure that the book you are holding in your hands actually comes from a bookstore?

After this conclusion, we would like to give the floor one last time to Alan Moore himself:

Hope is always the only rational position, in that to give up hope of success is to guarantee failure and, in the event that the worst happens, it is surely better to go out knowing that you resisted it and struggled your very best to prevent it from happening. So, yes, there is always hope. But, yes, I fear that the world is inevitably in for a gloomy period, and the hope is that we can survive it and build something better from it.

If we wish to have an inhabitable future for us and our children and their children, then might I quietly suggest we stop electing and tolerating obvious fascist buffoons because we think they’re entertaining characters, as if they were housemates on Big Brother. This isn’t reality TV. This is reality, or what’s left of it. Let us instead protest and rail at these dribbling Nazi idiots to our last breath, rather than beam stupidly as Elon Musk ‘sends his heart out to us’ Nuremberg style. Let us point out that they are suicidal cretins when they insist that climate change is a Chinese hoax. Let us not give these witless fuckers an inch.

And, more important than condemning the forces driving this multi-faceted disaster, let us take responsibility for ourselves and our communities. Let us for God’s sake stop relying on these leaders and their self-serving social structures that lead us nowhere save into the abyss. If we want things to exist – things like proper education, health and welfare services – then let us give our energies, our time, our money, our art, to the numerous community projects that are springing up of necessity and attempting to counteract these privations of the state or the toxic world it has created. Support environmental movements and protests, stand up for the rights of minorities and women at a moment when those rights are being clawed away from them by the horror story/laughing stock currently in the White House, form Arts Labs or start fanzines in recognition of the fact that we should probably think about providing our own art and entertainment too, and do something, some little or big thing to make the world around you more like the world you want to live in. Good luck.

Yves Potin 2025