What does it mean to be rational?

We are initially tempted to equate humans with rationality, since they are the only beings on Earth endowed with reason – the question then becomes whether humans demonstrate rationality, and therefore, what this concept even means. Is conscious thought sufficient to exhaust its meaning? Knowing what I am doing and why I am doing it, is it enough to act rationally? Clearly not. I am capable of reasoning and acting in accordance with the principles I set for myself, but it does not mean that such principles are rational – particularly in the pursuit of ways to satisfy my desires, which can override reason.

Exploring the meaning of this notion of rationality will therefore consist of comparing it with its opposite – the irrational and its many forms, this Other of reason. But it will also be a matter of distinguishing the rational from what is merely reasonable.

1 – Life on Earth is irrational

Human reason is capable of thinking, that is to say, understanding, natural phenomena. They give us a first glimpse of what the irrational is, which has nothing to do with the inexplicable. Nature is indeed the realm of chance, of that which has neither meaning nor purpose. Everything we know and understand about life shows us a total absence of both meaning and purpose—indeed, can we not already establish a synonymy between meaning and purpose? Does life on Earth have a goal, a meaning? Everything we know about it objectively shows us the contrary. The billions of years of evolution of living things are based on a cellular structure that could have been different, and serve no purpose, since everything we know about evolution eliminates the idea of an author who would have set an end for this immense whole that is life.

This evolution is marked by so many accidents and contingencies that it is impossible to see a final destination. Evolution is irrational; we have a real, albeit limited, understanding of it.

For example, the Permian-Triassic extinction is the largest mass extinction of living species for which we have any record, caused by immense volcanic eruptions during the formation of the supercontinent Pangaea. The continents we live on today resulted from the breakup of Pangaea, which also occurred with cataclysms. Like pieces of cork floating on thick mud, they eventually collide in extremely slow motions.

The impact of the immense asteroid in what is now the Gulf of Mexico is further proof of this contingency. It triggered the fifth great extinction, that of the dinosaurs. To see a transcendent cause in the fall of a stone, even a cosmic one, is the very definition of superstition: to link, by means of a supernatural being not found in any experience, events that have no connection to each other.

The sixth mass extinction, for which we are responsible, doesn’t even represent a global end imposed by humankind. We can retrospectively reflect on and understand the consequences of historical processes that culminate in what we call modernity. But humanity has never explicitly set out to destroy everything as it does now. How, moreover, could a creator God be the cause of a process that leads to a being whose activity precisely results in the destruction of that very “creation”?

Life has no reason for being, it has no author.

It is a void of meaning and purpose that we are objectively confronted with; it is not a belief. We explain and understand the nature of life and its evolution, even if this knowledge has many gaps. This is precisely why so many scientists get up in the morning and dedicate their careers to understanding and knowing all that we do not know. There is no belief involved, but rather an approach, a will to knowledge that research attempts to fill. Everything we find reveals an absence of meaning behind processes that are not finalized, that have no author who has set an end: the history of our planet Gaia is irrational, yet knowable.

Finding meaning in what has none, postulating significance despite the obvious absence of it—this is indeed a constant of humankind, particularly based on cosmological illusions such as apparent astral motion. It took thousands, if not millions, of years of contemplating the heavens to understand that we are in motion, and thus at the center of nothingness in a meaningless universe. The gods do not inhabit a sky populated by an entire imaginary bestiary; they are simultaneously empty and vaster and richer than anything we could have conceived by projecting illusory constructs onto them.

2 – Man is not simply reasonable

A rational being is capable of consciously setting ends through its will. Transposing such ends to the scale of the universe is called anthropomorphic illusion, as we have just seen. But is this reason truly uniquely human?

One might argue that spiders and beavers also act with a purpose in mind, namely the construction of their means of survival, just as we increasingly observe the inner workings of living beings that never cease to amaze us. It is difficult to precisely define the meaning of the word “knowledge” in the observation that a spider “knows” what it is doing, except that this knowledge is instinctive and not rational. But what about beyond the spider? Do higher apes, large cetaceans, even those adorable beavers, act in a purely and strictly instinctive manner?

In this respect, our pride is such that we find it extremely difficult to accept, even within the realm of scientific research, that reason is not limited to Homo sapiens sapiens. We are only just beginning to understand and accept that the lives of Neanderthals could have been far richer than the stone artifacts we have been able to find, and that they included a cultural dimension spanning hundreds of thousands of years (Marcel Otte ‘s short book provides an excellent introduction to this subject).

But let’s begin by asking ourselves whether humankind is truly as rational—or reasonable—as we think. What is the role of the irrational within us? Here again, the irrational is clearly distinct from the inexplicable, even if it can often be very difficult to explain or understand certain actions. “I did it because I wanted to”: this is found in children, who are quite capable of thinking and finding ways to satisfy a desire by doing what they know perfectly well is foolish. But we don’t find this only in children; the power of desire or passion often serves as an excuse, if not a justification, for criminal acts. “I can’t help myself.” This subordination or submission of reason to desire falls under the category of the irrational. The end being pursued does not stem from reason but, in the extreme examples we can consider, from perfectly knowable pathologies.

Can we call a serial killer rational? They may be exceptionally intelligent individuals who can consider their goals valid, even if they contradict everything society deems just. We can thus say that these are indeed reasonable beings from whom society seeks to protect itself. Plato, in his Gorgias, constructs a well-known paradigm with the famous character of Callicles, who defines culture as a means of protecting oneself from the force of the strong, the weak being strong only by virtue of their numbers. Is there a conflict of rationality here? Is rationality itself merely subjective, just like the goals that individuals and groups set for themselves?

At the other end of the spectrum, the writer Maxime Chattam offers us a striking portrait of serial killers, particularly in a novel like The Devil’s Patience, where, beyond a mosaic of criminal madmen, there is one person who is perfectly lucid about the motivations behind his actions. It is no coincidence that he is portrayed as someone whose profession is precisely to understand, if not heal, humanity in its darkest aspects: a psychiatrist. Is such a murderer rational? Clearly, his intelligence grants him considerable power, especially in manipulating others.

Here, then, is the other side of rationality. The use of reason for strictly subjective ends in their criminality: “The law of the strongest. I freed myself from my impulses and understood that it is by fully expressing them that I am alive” (The Devil’s Patience, p. 546). This is clearly yet another instance of the subordination of reason to vital impulses that are not rational.

The power of the strong, elevated to the status of a societal project, raises the question of the rationality of such a project, and therefore the very nature of what we call rational. Is there rationality in Nazism? As we have just seen, we cannot conceive the success of a criminal project without reason playing a role. In this case, mass extermination. What is profoundly troubling is admitting its rationality when we can only observe that intelligence is indeed at work. Behind projects in which human reason has distinguished itself as a capacity for collective, political organization, we find here clearly criminal ends. There is a clear rationality of means but not of ends, and it is in this that Nazism can be considered irrational. It is always the same human reason at work, in a completely perverted way precisely because it serves ends that are absolutely not universal: the domination of one part of humanity that exterminates another.

Far removed from the pathological dimension of serial killers or mass murder, it is clear that humans are capable of reasoning, if not of being rational. Numerous examples can be considered of how humans reason, or carry out projects that can be considered reasonable, whether individually or collectively.

To be reasonable is, first and foremost, not to immediately satisfy all one’s desires; it is in this sense that we say a child is reasonable, that they know how to reason. The ultimate goal is thus not always that of rationality, but rather that of desire, the satisfaction of which is postponed to a later date, certainly to be even broader and more intense. If the ultimate goal remains that of desire, then the question of what constitutes a rationality of ends remains entirely open. For example, where is the rationality in the consumption of alcohol, particularly when it is presented as a socially and culturally valued practice, with the well-known deadly consequences? “Wine is not like other alcohol,” some will say. Absolutely: it makes people alcoholic. Is that rational? One might reply that reasonableness lies in exercising restraint in the satisfaction of pleasures, but the meaning of rationality remains just as obscure.

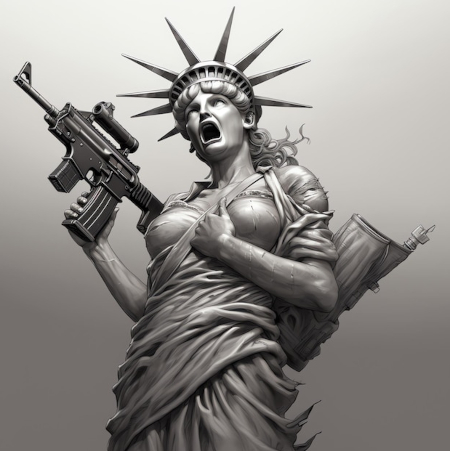

Is it reasonable to leave your home armed? To install alarms or even traps? It’s prudent; reason dictates it. But is it rational? Particularly in questionable social contexts, the freedom to bear arms can lead to genuine activism. It is nonetheless difficult to judge as rational the consequences of a constitutionally guaranteed freedom that causes thousands of deaths each year. It is even dangerous to claim that arms dealers defend only their own interests and not the overarching interest of civil peace. Indeed, we cannot establish civil peace because individuals are incapable of rationality in their actions. They do what they deem reasonable. They are human.

3 – The universality of the rational and the particularity of the reasonable

The contradiction between individual ends, which may be similar in many individuals, and a collective interest that is debated and would transcend the sum of individual desires, reasons, or interests, is expressed in numerous and complex problems that are clearly political. Let’s consider some other examples.

The French pension system gives rise to systematic social conflicts whenever its financing is considered. These are conflicts of legitimacy between individuals’ desire to stop working in order to fully enjoy their remaining years and society’s ability to finance this. These conflicts, often involving significant social pressure, end with social actors reaching a mutually acceptable solution.

This, however, foreshadows the next social crisis when the financing system itself will need to be revised because it will no longer be sustainable. Where is the rationality, if it is even possible to find it? It is far better to speak here of reasonableness or consensus rather than rationality.

This example has limited scope, but humanity shows us similar things with problems of a more considerable magnitude.

The history of Brazil shows us the constant pressure exerted on the natural environment by groups and populations seeking their livelihoods through deforestation—that is, the destruction of what constitutes one of the lungs of our planet. Here again, the challenge is to reason, to find ever-shifting balances between competing demands, each claiming legitimacy, and some capable of resorting to violence to achieve ends that are merely particular. How can we reason with social actors? And what would a rational solution look like? Clearly, these two questions are not the same, and therefore, reasonableness and rationality do not have the same meaning. We are perhaps beginning to glimpse that the universality of rationality radically surpasses, if not transcends, reasonableness.

A third example clearly highlights how the diversity of human societies and cultures leads to unstable equilibria stemming from a fragmented history beyond human control. From real and immense progress in our understanding of nature, made possible by reason, we have arrived at the construction of weapons of mass destruction capable of destroying the planet countless times over. There is something reasonable about this, in equipping ourselves with the same weapons as our adversary, in the balance of terror. It would be utterly irresponsible for politicians not to equip themselves with the same means of destruction as an enemy we know to be ready to invade us. This enemy is prepared to destroy what we are, for ends it considers entirely legitimate. Where is the rationality in the arms race?

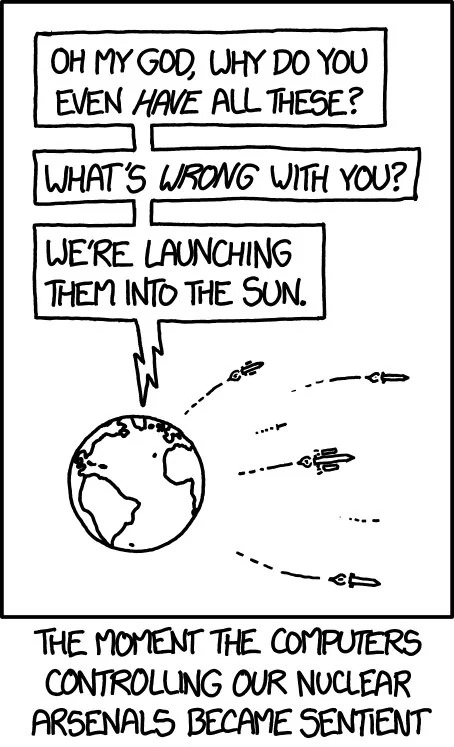

There is much speculation today about the dangers of artificial intelligence, but let’s suppose for a moment that it becomes rational and self-aware. How would it judge us?

The real danger with the development of AI is that it could behave exactly like us and take itself as the purely subjective end in all its actions. In doing so, it would give itself the means to exterminate humanity. Such a representation of AI is illustrated in the movie Terminator, among many other examples. There is a conflict there between the ends set by self-aware beings, knowing that the ultimate end these beings set for themselves is themselves: the machine versus the human. Frank Herbert’s great Dune series is based on the absolute rejection of such technological objects. Thus is staged the continuous wars waged by human groups, each pursuing contradictory goals: the Atreides and the Harkonnens.

But what the image above suggests is actually a truly rational AI, one that reaches an universal truth of which we are already fully aware but incapable of putting into practice. What we do with our knowledge is mad, sick, and devoid of any tenable rationality, since we are unable to establish a global end with truly universal scope, one that corresponds to an absolute truth: the survival of our planet. What is wrong with us? Why do we even possess such weapons?

Isn’t this reason clearly irrational?

This something so deeply disturbed within humanity, is it not it the contradiction between its rational knowledge and its actions based on that same knowledge? If we are incapable of overcoming the contradictions between our political and social models, at the cost of risking the very possibility of life on Earth, isn’t this a clear sign that, from a practical point of view, we are incapable of the rationality we demonstrate in our ever-evolving understanding of the world?

It is reasonable to possess the same nuclear weapons as the neighbor across the river who is ready to invade us. And yet, it is completely irrational. This is clearly understood by the people who have lived and still live in fear of the bomb, of the apocalypse that their leaders, who develop these weapons using money taken from their citizens’ income, could unleash. Where is the rationality? Should we fear being judged by our own creation, which might finally prove rational in our place? Is this the danger of artificial intelligence, the potential for an even broader questioning of deadly ways of life that are reasonable and comfortable but utterly irrational?

4 – Rationality, scientificity and human complexity

The question arises as to what a universally satisfactory end might be from a rational point of view. What does it mean to act rationally, and for what purpose?

A clear problem of universality arises when we consider the ends that reason, as a faculty of action, can set for itself, confronted with this same universality in the results it achieves in terms of knowledge. This distinction between theoretical and practical reason is not new, but it is worth noting that it is indeed the same faculty possessed by all humans. We could even suppose, because of the universality of the knowledge that reason attains, that living beings entirely different from us, on other worlds, would arrive at the same science, since it would be founded on the same reason, if it were “simply” a matter of understanding the universe and its laws.

John Brunner, in one of his last novels, The crucible of time, paints a striking portrait of an extraterrestrial race living on a planet doomed to destruction in a highly unstable region of space. The entire story shows how they slowly, gradually, come to understand that they must leave their planet. And at each stage of this progression toward rationality, they encounter obstacles in constructing a rational understanding of the world, as there will always be those who cling to irrational and mystical representations of both reality and the cosmos.

The metaphorical scope of this plea for scientific rationality is quite clear. We have no shortage of examples of such constructions that can only be considered irrational, even though they may be subject to explanations.

Thus, conceiving of a profound unity among all religious traditions throughout history is not absurd, provided that the issue at stake is an understanding of human reality and what motivates such symbolic constructions. The work of Carl Gustav Jung is particularly illuminating in that he limits its scope to a strictly psychological investigation: understanding the human psyche, which transcends our conscious awareness. This always involves a rational approach, one that strives to be scientific, especially when it comes to understanding what possesses a truly mysterious dimension: myths, initiations, magical practices, visions, and apparitions. It is not a matter of denying what we do not understand and what seems to fall outside the framework of scientific rigor, or even narrow positivism. What matter is taking facts into account, however surprising they may seem.

The irrational lies in attributing to these facts a supernatural, transcendent reality that nothing has ever objectively established. An example of this can be found in the very large work of René Guénon. Through his immense erudition, he aims to establish this unity he calls Tradition, the non-human and transcendent origin of which he seeks to demonstrate.

Human history reveals the pervasive presence of mysticism, the search for an experience of what humanity calls transcendence, another reality that surpasses reason and the capacity for thought. Thus, experiences and accounts of other worlds, messages from beyond, multiply, all of which are presented as supposed proof of the limits of reason’s ability to grasp a reality that transcends the world we commonly experience.

But then, what about this possibility of inducing such experiences in a purely material way, by intervening in the human brain with plant-based or chemically synthesized substances that alter mental functioning? This doesn’t have a transcendent origin. We can even be considerably mistaken about the meaning of such experiences, which we call psychedelic. The great writer Aldous Huxley is certainly not one of the great proponents of the irrational or of magic, yet his discovery of psychedelic drugs led him to establish a link between what LSD produces and the mystical experiences that some people spend their lives seeking. In what way are such experiences contradictory to human reason? Isn’t it particularly dangerous to find in such experiences reasons to condemn that very reason?

Conversely, the irrational is part of human reality, which must be considered as a whole, and the richness of the imagination testifies to this complexity of humankind’s inner worlds. Artistic creation is inseparable from this dimension of the irrational, which Surrealism, to take a recent example, has extensively explored.

Conclusion: Rationality and Life

It therefore appears that modernity, which began with the Copernican-Galilean revolution and the foundations of contemporary science, gives rationality a universal meaning. This faculty of knowledge, which humankind possesses, leads to a representation of the world which is now widely validated by the practical applications it allows. In doing so, it relegates to the realm of the irrational a whole set of practices that are not inconsistent but for which there is no basis for establishing objective validity. To put it simply, if magic worked, we would know about it.

Kant’s work represents a major turning point in the history of human thought, as it justifies the autonomy of rational inquiry in understanding the world. Kant then extends his philosophy beyond theoretical reason to the foundations of human action. What is moral action, and what should we do? In this regard, he considers reason itself to be the ultimate goal of reason. “Act in such a way that your rational being is always at the same time an end and not merely a means to your actions.” Such a morality has received much criticism since, particularly concerning the problem of lying. But it is important to emphasize here that the Kantian categorical imperative has no meaning outside of life itself, and that this life is given to us here and now, on the planet where we live, regardless of the rather problematic prospects of an afterlife.

This has been extensively discussed in another article available on this same site, which highlights the consequences of a non-teoleogical representation of the world. The question now is : which is the rationality at work behind the environmental destruction for which we are responsible of, within the very context of modernity. All of the above helps us understand that the “Cartesian project” of technological mastery over the world is irrational; we can now measure its dimensions and consequences with the benefit of hindsight. Even if Descartes could certainly already understand that his theory of animals as machines is utterly absurd. What rationality lies in the ever-increasing destruction of the conditions for life on Earth? The same article presents how John Brunner, once again, portrays humanity as a blind herd, to borrow the title of the French translation.

But this implies that the foundations and purpose of rational action can be none other than Life itself! While the progress of rationality as a means of understanding the world has been immense over the past four centuries, what this knowledge has enabled is not a rational project but rather an increase in power for subjective, purely human ends that threaten the very survival of humanity and even life on Earth itself. No lengthy explanation is needed today to prove this. With the absolutely enormous power at our disposal, we cannot rationally set ourselves any other goal than the preservation of Life on Earth.

Life and its evolution are irrational; there is no intelligence at work on Earth presiding over the construction of biodiversity. Except for ourselves. This does not allow us to objectively consider ourselves as the end of Nature, which has no end, but it does lead us to question the practical meaning of the reason within us, the meaning of what we do, relying on this faculty by which we define ourselves.

Acting rationally is preserving Life we receive as an inheritance, as if we were the meaning of the billions of years of evolution that have allowed us to be rational.

Let us leave the conclusion of this reflection to someone who has dedicated his life to defending such an obvious truth, David Foreman:

“It’s very difficult in our society to discuss the notion of sacred apart from the supernatural. I think that’s something that we need to work on, a non-supernatural concept of sacred; a non-theistic basis of sacred. When I say I’m a non-theistic pantheist it’s a recognition that what’s really important is the flow of life, the process of life…. [So] the idea is not to protect ecosystems frozen in time … but [rather] the grand process … of evolution…. We’re just blips in this vast energy field … just temporary manifestations of this life force, which is blind and non-teleological. And so I guess what is sacred is what’s in harmony with that flow.”

Yves Potin 2025